![]()

A JOB NEAR HOME

by Allen Windross

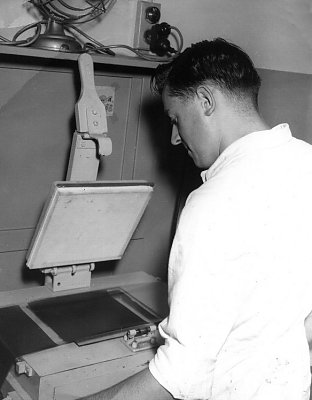

| Allen Windross at the photo printer. Most of the photographic and reproduction equipment was built by aircraft engineers in the hangar workshop. (Photo: Allen Windross) |

|

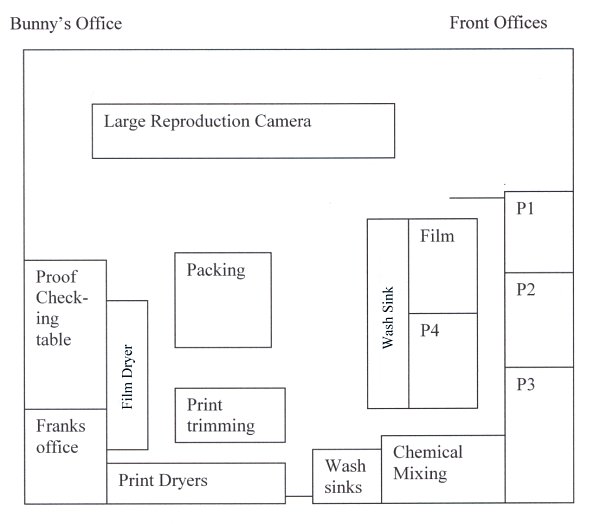

In early May 1954 I saw an advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald’s ‘Positions Vacant’ column for a junior male to join the staff in the Adastra Airways Photographic Laboratory at 41-43 Vickers Avenue Mascot. That address was four doors from my home at 33 Vickers Avenue. Aged 15 years I thought the role was made for me and so I walked through the famous Adastra etched glass doors and applied for the position. The Photographic Manager, Frank Schneider, interviewed me. On Friday 21 May Frank sent a messenger to tell me to come back to his office. He told me that I had the job and handed me a well-worn white technician’s wrap coat. My salary was to be £5/5 per week less three shillings tax. Monday 23 May I reported for duty and was told I was to be trained as the ‘Chemical Boy’ making up batches of chemical solutions to be used as developers and fixing agents. The white coat was very necessary as the chemicals left deep stains if splashed onto clothing. There were other duties as well including cleaning floors and helping out wherever required. Great emphasis was put on keeping the place clean and there was a tidy-up period at the end of every day. The other Photographic staff included Jack Townsend, Bill Gow, Gordon Stack and Joan Pearce amongst others. The Section was laid out somewhat like this:

Film produced by the aircrews came in and was developed in the darkroom labelled ‘Film’. After fixing and washing the film was dried on machines near to Frank’s office. These machines gave out a sound of equal decibels to a Constellation engine and I am sure my present deafness started then. A set of proofs of the negatives was then produced, in one of the four print darkrooms labelled P1 to P4, for Frank and his chief Lou Pares to check against contract maps. The work then involved producing quality prints of each negative that were subjected to developing, fixing, washing, drying and trimming before being packed in delivery cartons. The print trimming was performed on a wooden cover over the top of a billiard table. I saw this table used for games only when the Christmas Party was held in the room. P1 also held a big enlarger. The base platform of this enlarger proved to be a great card table. P2 had a smaller enlarger. The basic equipment in each darkroom was a contact printer and a large lead-lined sink that held trays for developing, rinsing and fixing. Work in the P1 to P4 rooms was carried out under orange lights while the film room used a faint red light. Each of the darkrooms had a sliding door opening onto a hallway or corridor that had two entrances, both marked by black curtains. I soon learned that the workload of the section fluctuated because if the aircrews could not fly due to cloud or otherwise inclement weather no film arrived and there was no work. Such downtime was filled by chores such as major cleanups and painting as well as cleaning the cars owned by Frank and Lou. If the aircrews remained grounded though, even the chores were fully exhausted and we would gather in P1 to play cards. I was soon proficient in games like Euchre and Canasta. Eventually the weather would improve and film would again start arriving. If this coincided with the last three months of the financial year then we would go from no work to overtime. This was because the mainly government clients would want to ensure they spent their budget allocation before 30 June. I can still recall the dispiriting emotion that flowed while cleaning up on a Sunday afternoon, after having worked nights and weekends, knowing that I had to be back the next morning to do it all again. If allowance is made for inflation and changes to my age rates of pay, the extent of overtime can be detected from my annual income records:

If is doubtful the darkrooms would have been permitted in today’s workplace safety environment. The chemical solutions and consequently the air were frequently bitterly pungent. I can recall three personal health issues that almost certainly related to the workplace. Firstly a major skin eruption on my left forearm that required hospital treatment. It took weeks of treatment with the hospital pharmacist’s ointment to clear it up. Even so, the slightest irritation in the next few years would see the condition return. The second was when the community compulsory chest x-ray found a cloudy area on my lungs. It was not TB but a condition not recognised by the doctors. Decades later I was told my lungs still did not perform to their capacity. This event led Frank to seek and install improvements in the darkroom ventilation systems. Finally I started to get recurring severe bouts of infected pharyngitis during the early 1960s. It was this that led me to look for a new career. There were other dangers around, especially if you became a little careless. I had at least three electrical shocks from a combination of liquid and power. One threw me to the other side of a darkroom. The Reproduction Camera had a motorised travel along a screw centre rod. Bill Hohnen was working with it when the end of the rod became entangled in his trouser leg at the thigh. He could not reach the on/off switch and called out. Joyce Owen heard his call and screamed out for me. I reached the switch and reversed the travel as Bill was about to pass out. The combination of the fabric and the metal rod could easily have resulted in major injury. As it was he had a sore leg for a while. Frank was a good manager: firm but fair. Mostly the team got along in harmony and it was a friendly workplace. Social events were held from time to time and one of these had a great bearing on my life. Joyce Owen had joined the team of females that looked after the print drying and trimming. She was the aunt of the Australian tennis great Lewis Hoad and was involved in the sport herself. Joyce proposed a social tennis night that was held at courts on Botany Road at Mascot. Everyone had a great time and it was suggested a tennis club be formed. A number of the staff lived in the St George district of Sydney and it was felt reasonable to find a court in that area. Joyce found a court behind a private home in Alfred Street, Ramsgate and we were away. The club was a success but with time there were fewer Adastrians playing although Bill Hohnen and I remained steadfast. Acquaintances of players joined up but eventually in 1960 it was decided to advertise in the St George Leader for locals to join. Three young ladies came along and one of these later became my wife. Bill Gow was an avid Socialist and he sometimes caused problems for the management. Once he found that Adastra was paying under the award rates and on another occasion that the company should be laundering the protective coats and overalls at its expense. At one point Bill resigned and took a job doing retail developing and printing. He said he thought that was a more responsible thing to do in society. After a time he returned to Vickers Avenue saying that, after reflection, Adastra’s work was building the nation. I was an avowed reader and Bill encouraged this with all types of left leaning publications. Jack Townsend who at one stage lent me his enormous tomes on the life of Napoleon Bonaparte balanced this to some extent. The work was about the size of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire and just as detailed. About the year 1960, given the sensitive nature of some of the work, the staff were subjected to an ASIO check. I wondered how Bill would get on but once I had the forms to fill in I saw that it was mostly about ensuring that you could list some referees, had Anglo-Celtic ancestry and had not lived or worked in some dubious country. As far as I know all staff but one passed the check. He was an Eastern European migrant who detested Communism. This was probably an ironic outcome. The role of work in the isolation of a darkroom for hours did lead to some hi-jinks at times. One often repeated wintertime jape was to fill a large jug with cold water and lie in the wait for a fellow worker as they entered the darkroom corridor through the black curtain. They could not see the cold water dousing coming. I received and returned a number of these and at one stage was continually victorious over Ken Snell. One especially cold day Ken heard me go out to the drying area and lay in wait for me to return. He hit the target with the lot but it was Frank Schneider not me. Frank was dressed formally: suit pants, shirt/tie and woollen no sleeve pullover. He said nothing, turned and went back to his office. Ken was left quivering, convinced he was about to be sacked. Frank though said and did nothing. Given he had played for the St George Dragons he had probably endured worse. No one in management at Adastra ever seemed to want to dispose of any redundant items and there were surplus pieces of equipment and stores packed everywhere. During some of the no-film times we located some old nitrate based survey films in a back storeroom. Under the guidance of Ken Snell we cut the leaders off the films and chopped the leaders into small pieces. The pieces were then crammed into aluminium 36 shot 35mm film cans. The type in use had a screw-on lid that rose to a peak. Holes were made in the base of the cans and the lid taped down well. We then made a fire under a launch platform in the Tenth Street playground. Once the nitrate ignited the can became a rocket. Our most successful launch saw the can climb about 200 metres and towards the East-West runway. Unfortunately a Qantas flight crew also observed the launch. Civil Aviation gave the company a blast and the rocketry experiments ceased. Frank encouraged the younger members of his team to go on to become camera operators in the aircrews. We tended to regard the crew with awe especially the pilots but we had an obvious affinity with the camera operators and I regarded many as friends. In particular the loss of Gordon Murrell in the 1958 Hudson crash at Lae made a big impact on me and probably deterred me from further interest in becoming a permanent aircrew member. Once the Eleventh Street hangar was allocated to Adastra we also came to know the ground crews much better. We would often walk across to say hello and look at the kites under service. Obviously we were cheek and jowl with sections like photogrammetry and drafting and saw those people for lunch and tea breaks. Within our own little group we were pretty close and often socialised as a team. Bill Hohnen and I took a most enjoyable Gold Coast holiday together.

Allen Windross |